A story of oops

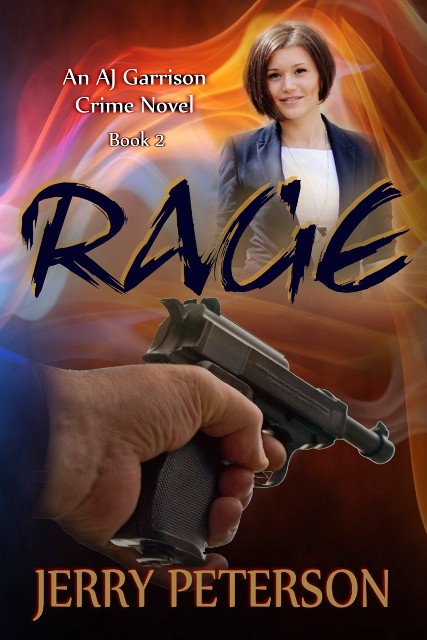

Book covers can be tricky. Take a close look at this.

Now some background. The murder weapon I chose for this story was a German Luger. That might be a good element for the cover, I told my cover designer. She found the image you see. And it's excellent.

A bonus now. Notice the weapon is held in the left hand of someone. I hadn't told my designer that my shooter was left handed. Is she psychic? Maybe.

Anyway, I brought the cover to my writers group, to get their reactions. And one of my colleagues, Clayton Gill, who knows guns, said, "Do you know what that pistol is?"

A Luger, I said.

"No. It's a Walther."

A Walther P-38.

I liked the cover so well, that, thank you to 'Find and Replace', one click and Luger became Walther throughout the manuscript.

Here's

the thumbnail of the story: Before there was Newtown and Shady Hook Elementary. . .

Before there was Columbine. . .

There was Morgantown.

Morgantown Consolidated High School.

1969.

A student takes a gun to school and murders one of his teachers in front of a classroom filled with students. Criminal defense lawyer A.J. Garrison finds herself appointed to defend the boy.

It’s her first capital murder trial, and she’s going to lose. No doubt about it. The only real question for Garrison is can she save her client from the electric chair?

So here's chapter 1.

Seven o’clock

Remember the Alamo, remember the Maine, remember me . . .

Those words–a kind of memory stone–rolled through Thad Cardwell’s mind as he turned the blade of his art knife against a whetstone. It wasn’t his art knife, exactly. He had put it in his pocket during class and just managed not to remember to leave it at the end of the hour–borrowed it one might say.

Besides, it was sharper than anything he had and sharper still now, as sharp as a scalpel. He drew the knife through a sheet of paper, cleaving the page in two.

Neat.

The boy–tall, gawky, his hair a thatch that broke teeth out of pocket combs–opened his history book. He sliced away at a pattern he’d drawn in the center of the pages, deepening an excavation, humming aimlessly, tunelessly as he worked. He’d wanted to be in the choir, but when he couldn’t tell whether a C was above or below a G, the choir director thanked him and suggested he pick up another shop class.

Another shop class.

Right.

He’d ‘borrowed’ a small bottle of Elmer’s glue at the Ben Franklin store and pasted the edges of the book’s pages together so nothing moved as he deepened his incisions. He stopped and threw the new mess of scraps he’d cut from the heart of the book into a plastic bag. This he would have to dispose of.

Cardwell gazed at his work. He set the art knife aside and ran his hand around the inside of the cutout, pleased at how smooth the form was. The point and the blade on the art knife made all the difference.

And now the test.

Cardwell picked up the Walther P Thirty-Eight from the blanket beside him, not his gun. He didn’t own a pistol. He had ‘borrowed’ it, too, from the drawer where his uncle kept it and, last night, with great care pressed eight bullets into the magazine. Now he placed the gun in the cutout. Admired it.

A perfect fit.

“Thad?”

His mother’s voice, calling to him from downstairs. For as long as Cardwell could remember, it was his mother and he, and his older brother, but Rob was gone now, in the Army, somewhere in Vietnam.

“Thad?”

“I hear ya, Ma.”

“You gonna have breakfast before you go to school?”

“Don’t think so. Not hungry, really. Besides, John’ll be by in a couple a minutes.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah.”

He closed the cover of his history book and put it in with the others he intended to carry to school. Cardwell took his plaid jacket from the bedpost and pushed his arms into the sleeves. The jacket, shabby from age and wear, had come down to him from Rob. He took his blue-and-white striped cap from his jacket pocket and slapped the cap over his hair. Kids called it his feed cap and it was. His uncle had gotten it free from the co-op mill.

A white cat rubbed up against Cardwell’s pant leg.

The boy bent down. He tickled the cat under his chin, and the cat purred with gusto.

Cardwell swept him up, cradled him in his arm, and stroked his belly, the cat smiling its perpetual smile.

“Kit, I gotta go.” He opened the window and set the cat outside, on the roof over the porch. “See ya when I get home from school, huh?”

Cardwell closed the window and grabbed up his books and binder, and tucked them under one arm as he clattered down the stairs.

“Thad, you all right?” his mother asked from back in the kitchen.

He stopped at the front door. “Yeah . . . yeah, I’m all right.”

“You hurry home after school. It’s church night, tonight, you know.”

“Yeah, I know.” He pushed on outside and down the stone path to the gravel road.

Thaddeus Pease Cardwell. Thaddeus had been his grandfather’s name, an honored name, his mother had said. Pease, that was her maiden name, and she didn’t want it forgotten. She had been an only child, and there was no one else to carry the name on.

Thaddeus Pease Cardwell, TP to some. Cardwell knew what that stood for. Pees-alot to others. He and John Gilland were called the Hick Club, not by their choice, but because both lived so far out from Morgantown, in Teller Cove, he up under the lee side of Cullowhee Mountain, Gilland further on, on Reed’s Creek below Long Ridge.

The two had ridden the bus to the county high school, always exiled to a front seat–behind the driver–until Gilland turned sixteen and his brother went off to the Marines and left him his ’Fifty-Two Chevy half-ton, not a bad vehicle on most days, but when it rained, water splashed up through the rusted-out floorboard on the passenger side. Cardwell had gotten into the habit of putting his foot over the hole, but still there were stormy days when he walked into school with one pant leg wet up to the knee.

Cardwell heard the half-ton rattling his way. Rattling, yes. Much of the joint between a rear fender and the truck box had rusted away. Gilland had patched it with Metal Weld, advertised as a body-shop super-glue, but that had broken. Next he’d taped the joint with duct tape, but that hadn’t held either. Cardwell had talked to Mister Romines, the ag teacher, about bringing the truck into the shop, to weld new sheet metal under the box and the fender.

Cardwell waved as Gilland pulled to the side of the road. Gilland shoved the passenger door open. An odor, like old gym socks, drifted out. “Gitcher math done last night?” Gilland asked as Cardwell slid onto the seat and slammed the door shut.

“Huh-uh.”

Gilland, a chunky youth topped by a Cincinnati Reds baseball cap that kept his unkempt mane in some sort of order, pushed the floor shifter into first. “Well, why not?”

“I was workin’ on my history.” Cardwell pushed the book up on the dash.

“Well, what the hell for? We ain’t got a test in there for another week.”

Cardwell said nothing. He just leaned his elbow on the door’s armrest and gazed off toward the side of Cullowhee, his eyes not taking anything in.

Gilland shifted the transmission into second. “You kin copy my homework if you want.”

When Cardwell didn’t answer, Gilland came back with, “You in some kinda funk?”

“Maybe . . . yeah, I guess I better copy your homework.”

________

Get Geronimo, get Pancho Villa, remember me . . .

A new set of words rolled through Cardwell’s mind as Gilland busied himself with herding the truck off the pavement of the high school’s entrance road and into the gravel lot.

The building before them lifted the spirits of no one. Plain brick and flat roofs, it had the look of a prison–industrial cheap, cheaper than anyone knew at the time the school was built a decade previous. The contractor had scammed a fifth of the funds, covering with low-grade materials and shoddy workmanship.

The building showed the proof–cracks in the foundation and walls, roofs that leaked. When it rained, the janitor and the principal raced through the building, distributing buckets to teachers to catch the drips and downpours. In one upstairs hallway, students had to squeeze to one side to get past a tub the janitor put out as a water catcher. On one of those soaker days, students dropped rubber ducks in the tub, and one a block of wood with a paper sail on which he had printed ‘SS Morgantown High.’

Gilland pulled the handbrake up and turned off the key. “Five minutes. We better git on inside.”

Cardwell didn’t answer.

Gilland got out and turned back. He gathered up his books and his sack lunch. “You comin’?”

“In a bit. Thinking of a poem. I may write it before I go in for English class.”

“Old Lady Bevins don’t care shit for yer poems. Hell, she don’t care shit for you.” Gilland closed the door. He called back through the open window, “See ya in math. And how ’bout you catch me for lunch, huh?” He held up his brown bag. “I brought extra.”

Cardwell waved him on.

Gilland galumphed away. He disappeared inside with the last of the late rush.

Cardwell opened his binder. He took out a pen and touched the point to his tongue, not because he liked the taste of ink, but out of habit. Then he wrote a title, ‘Escape,’ and dashed off five lines. He read them back, smiling as he did, pleased with the meter and the a-b, a-b-c rhyme scheme.

The bell rang, and he closed his binder.