|

A new James Early Christmas collection

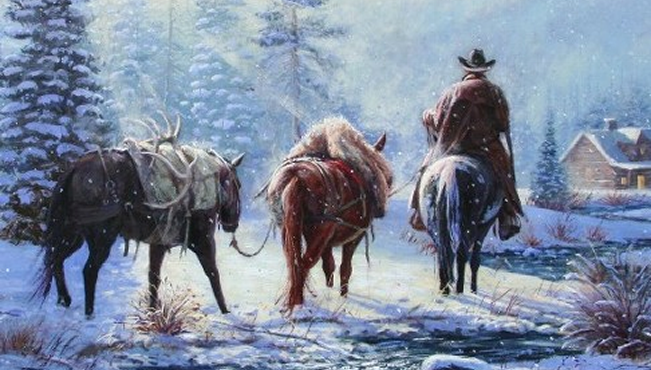

My favorite A guest looked over my 10 books on the table at a recent event and asked, "Of all the characters you've created, which is your favorite?" That's like asking a father, which child is your favorite? Whatever your answer, someone's going to be upset. It took some moments as I ran through the list before I said James Early. Early is just himself, no pretenses, a cowboy trying to do the right thing, a sheriff only because he needs the paycheck. In the first story in this collection, Early is doing what he likes to do most, check on his cattle in distant pastures . . . and it just happens to be Christmas Eve. Here's a flavor of that story.

A Night for Miracles Early tore off for his horse. He pitched the calf across the roan’s shoulders, swung into the saddle, and spurred up the side of the ravine. Early let out a piercing whistle, and his dog unloosed himself from the cow. He raced away, she, blood streaming from her nose, hot after him, churning snow only to give up when the blur of black fur disappeared over the lip of the ravine and into the gloom of the evening. Fifty, maybe a hundred yards on, Early reined in his horse. He studied the calf that laid before him, patches of frozen afterbirth still clinging to its hair. Early worked a gloved hand over the calf’s ribs and legs, feeling for breaks. He rubbed the calf’s face. “Malleable little critter, aren’tcha?” The little Hereford flicked its tongue out in a languid attempt to catch Early’s hand, to draw it into its mouth, as if the hand were a teat to be sucked. “Hungry? Well, we’ll getcha home, get some milk in you. Gonna be a cold ride, though, and you’re already chilled to the bone.” Early pulled off a glove. That freed the fingers of one hand, and he twisted around and undid the leather laces of the canvas roll behind his saddle. Early shook the canvas out. He swaddled the calf in it as best he could, the cold of the night making steam of his and his horse’s breath as he worked. Helluva way to spend Christmas Eve, Early thought, riding from haystack, to draw, to grove of scrubby trees, checking cattle, the shadowy presence of his wife with him. But she had died months earlier in an awful accident, and he just minutes away. If only he had been faster– Two yearlings stranded in deep snow broke him out of his mental stew. Early roped first one, then the other and dragged each out to keep them from becoming coyote food. This little calf faced the same fate had not he stumbled on it and its momma. Some momma that wild one. Early figured get her fat on grass come summer and ship her to the meat packer. Be rid of her. He rubbed the calf’s shoulders. This one he’d have to hand raise because he didn’t have a dairy cow to put the calf on. What are you anyway? Early pulled the calf’s tail up and checked. Uh-huh, a heifer. He kneed his horse, and she stepped out for home, the Newfoundland trailing behind, shagging along in the horse’s track rather than breaking trail for himself. Sure sign the dog’s tired, Early thought as he glanced back. He looked up, too, at the sky swept clean of clouds by a front that had come through the day before, at the moon a shade above the eastern horizon, the moon a coppery yellow, flattened on top as if it had been a ball of buttery dough slapped by a giant. If Early had to be out, at least it was a nice night–no wind. As his horse plodded on, he watched stars spangle themselves out in the darker regions of the sky. He could navigate by them. As long as he kept Polaris over his right shoulder, he’d eventually come out at home or nearby, striking the county road that would take him there. Half an hour he figured. Surely not much more. Ahead, in the light of the guardian of the night, Early saw the spidery form of a cottonwood that grew by one of the two never-fail springs on his ranch. A previous owner had cemented rocks around the spring to form a pool, so the cows wouldn’t muddy the water when they came in to drink. Early also saw a bulky shape in the tree and, when he neared the spring, the shape launched itself into the night–an owl. By its size, Early guessed a Great Horned or perhaps a Snowy that had come south from Canada to where it might better forage for rodents and rabbits. Early guided his horse up to the pool and found it as he expected, iced over. He stepped down into the snow. Early hammered the ice with his fist. He broke open a hole and pitched the chunks of frozen water away, and drank first. When Early moved back, mopping the sleeve of his mackinaw across his wet chin and droopy mustache coated with ice, his horse pushed up. She drank long. The dog did not. Instead he satisfied whatever thirst he had with mouthfuls of snow. Early rubbed his horse’s face after she lifted her muzzle from the water. “Road’s just over the rise, old girl. We’ve not far to go.” With that he swung back into the saddle, and the trio pushed on–quartet if you counted the calf. But the calf, stiff from the cold, lolled where it laid across the shoulders of the horse, barely aware of its surroundings. When they topped the rise, tableland stretched before them, snow-covered bluestem pasture on Early’s side of the county road, wheat and corn fields on the other, silvery in the moonlight. That road came over from State Seventy-Seven to the east and meandered on to Leonardville–a town of no consequence except to the people who lived there–the only things along the road a couple ranchsteads, three farms, and the Worrisome Creek Baptist Church where Early, on Sunday mornings and Wednesday evenings, sat in a back pew listening to Hubert Arnold preach, the man he liked to call the Great Bear of the Plains. Christmas Eve service, he could be preaching now. A lone pair of headlights came Early’s way from Seventy-Seven. He watched them as his horse walked along, watched them worm their way around two bends, then jerk to the north and go down. Into a ditch? Early wondered. He knew it had to be when he saw billows of steam piling up into the night sky. Early spurred his horse into a gallop. That jarred the calf, but he kept a hand on her back so she couldn’t be pitched off. Early hauled up on the reins when he neared his line fence and the ditch on the other side, the ditch that held an old Hudson captive, snow up to the vehicle’s hood. He bailed from the saddle, jumped the strands of barbed wire, and plunged down, his chaps knee-deep in the snow. Early wallowed his way to the driver’s door and wrenched it open. In the shadows, he saw two people, a man behind the steering wheel and a woman beyond, she clutching something and whatever it was, it squalled. The man held a hand clamped over his nose, blood discoloring his fingers. “You all right?” Early asked. “Busted my beak.” “Your woman got a baby there?” “Uh-huh.” “Your baby all right, ma’am?” The woman leaned forward, rocking something in the blanket, shushing at it, cooing to it. “Just scared. I held him tight, kept him from hitting anything.” “You, ma’am, you all right?” “Think so.” “What you all doing out here?” The man twisted toward Early. “Going home.” “And that would be?” “Leonardville.” “Where you comin’ from?” “Manhattan. Mary Elisabet birthed our baby couple days ago at the hospital. They let her out tonight.” Early leaned down. He peered at the man. “You Joe Davidson?” “Uh-huh. An’ my wife.” “Heard you’d had a baby. I’m James Early. You know me. Joe, this isn’t the best night to be out and the worst night to be in the ditch.” “Hit something or a tie rod broke. I lost it.” “Not all you lost. That steam? Fella, you busted a radiator. Your car’s dead.” “We gotta walk then, huh?” “Well, maybe not too far. Worrisome church is about a half-mile yon way. Service there tonight, so we ought to be able to get someone to drive you all to your place. First, we got to pack that nose of yours, get that bleeding stopped. Come out here in the moonlight.” Davidson slid off the seat, a big kid in jeans and a short jacket and a fedora that may have seen a lifetime on someone else’s head before it came to him, the kid a couple years out of high school. Early kicked the car door shut to keep inside whatever heat remained. He motioned Davidson to lean against the fender. Early pulled his gloves off and stuffed them in his coat pocket. When his hand came out, it held a bandana. Early bit the hem and tore a strip away, then a second. After he rolled each strip into a bean shape, he lifted Davidson’s hand from his nose and studied it as he wiped away as much blood as he could. “Keep your head up now. This is gonna hurt a bit now.” Early pushed one fabric bean into one nostril and the second into the other, Davidson wincing at the touch and the pressure. “You got gloves to keep your hands warm?” “On the seat by Mary Elisabet,” Davidson said, his voice nasally, stuffed. “Well, you wash your hands clean as you can in the snow, and I’ll get your gloves, and your wife and baby.” Early, waving his way through steam and the smell of alcohol anti-freeze boiling away, slogged around to the passenger side of the car, a pre-war job, a coupe. He opened the door and crouched down. “Mary Elisabet, I got my horse on the other side of the fence. How about you and the baby ride, and Joe and me, we’ll walk until we can get you someone to take you home?” The woman–a girl, really, now that Early saw her face more clearly–hugged her child to her chest. “I’m afraid of horses.” “You don’t have to be. Molly’s about as nice as they come, and she likes women and babies. Come on, let me help you to get out.” He caught the girl by the elbow and drew her outside. He reached back in for Davidson’s gloves, yellow work gloves like those Early wore around the barn. But when he rode, he wore fleece-lined leather gloves. Anything less in the cold was begging for trouble. “You got gloves, ma’am?” The girl shivered, giving Early his answer. “Well, here,” he said, “take mine.” He stripped his gloves off and snugged the girl’s hands into them. Early started away, going ahead, kicking and tramping through the deep snow, breaking a path for the girl, but she called him back. “We got a suitcase in the backseat,” she said. “It’s got some things for the baby and a menorah.” “We could leave that and get it tomorrow.” “No, it’s important.” “Well, all right.” Early chewed at his mustache as he worked his way around the girl to the door. He opened it, pulled the front seatback forward, and reached in for a pasteboard suitcase. Next to it, Early found something far more valuable–a blanket. He pulled both out, banged the car door shut, and went on around the front of the crippled car and up to the fence line, the Davidsons struggling along behind him. He set the suitcase and blanket over, in the snow on the other side. Hands free, Early pushed the top strand of barbed wire down. “Joe, you step across, and I’ll hand your wife over, all right?” “Yeah, I can do that.” Davidson eased over the wire. When he turned back, Early swept the girl and her child up in his arms. He passed them across to Davidson, but the hem of the girl’s dress snagged on a barb and ripped. “Whoa up.” Early caught the fabric. He pulled it free of the fence and followed across, swinging first one leg over the wire, then the other. Early, with the suitcase and blanket, and Davidson, carrying his wife and baby, pushed on through the snow to where Early’s horse stood waiting, the Newfoundland lying nearby. Early peered at the calf already on the horse and all the cargo he wanted to put up there. “Not sure how we’re going to do this,” he said to Davidson. “What’s in the canvas?” “Newborn calf. Her momma didn’t want her. Help your wife up in the saddle, would you?” Davidson moved up beside the horse. He slipped Mary Elisabet’s foot in a stirrup and helped her lever up, she holding her child tight–helped Mary Elisabet to sit side saddle. “I don’t like this,” she said as she settled on the seat. “Hon, you’ll be all right.” Early held the blanket out to Davidson. “She’s gonna be cold up there. What say you wrap her in this?” “Yeah, that’s good.” The kid flapped the blanket open. He lifted it at the midpoint of the long side up over his wife’s head. Early moved around to the other side of his horse. He caught an end of the blanket and, working with Davidson, tucked it around the saddle and brought the end forward, up and around the baby and the canvas-swaddled calf. Early’s hands felt the bite of the cold. He thrust them deep into his coat pockets and hustled forward. Davidson, toting the suitcase, came up the other side. The two met and moved along. And the horse followed, but the Newfoundland, instead of trailing behind, jumped out. He broke a trail of his own beside Early. “Miracle for us you were out here,” Davidson said. “Some of us believe Christmas Eve is a night for miracles.” “I guess.” “Your wife says you got a menorah in your suitcase. I’m thinking that means you’re not Presbyterian.” “Jewish, both of us.” Davidson gazed down at the snow he kicked before him. “Tonight’s the first night of Hanukkah. Took the menorah to the hospital so we could celebrate, you know, light the servant candle and the first candle if they didn’t let Mary Elisabet and the baby out, then they did. Know about Hanukkah?” “A little.” “The rabbi says it’s one of our lesser holidays, but I like to think it rates right up there with your Christmas. It’s a freedom thing.” “How’s that?” Early asked. “Couple thousand years ago, fella named Mattathias and his boy led a revolt so we Jews could worship our God, and they won.” “Your temple, wasn’t it destroyed in that war? Seems I remember that.” Davidson chuckled. “You do know something of us.” “Sometimes Herschel Weichselbaum and I sit in the back of his store. We visit, and he takes it on himself to make this poor Gentile knowledgeable on a thing or two.” “Mister Weichselbaum’s good at that. So he told you we rebuilt the temple?” “That he did.” “Yeah, had to be some big effort. Mattathias dedicated the temple to God, and that first night he lit a lamp.” Davidson smiled as he slogged along. Early wondered if it might be a memory. “A miracle,” Davidson said. “The lamp?” “Yeah. See, it burned ’round the clock for eight days, only our people had little enough oil to keep it going but that first night. Mister Early, Mary Elisabet and me, we wanted to celebrate that miracle, celebrate it at home now that we got a baby.” “Boy or girl?” Early asked, pushing along. “Boy.” “Give him a name?” “Christofer we’re thinking, after my granddad.” “’At’s a good name.” “Uh-huh, Christofer Davidson. Custom is to hand the generations down in my family. My granddad says we go back to early Israel days–the House of David.” “That is something. We Earlys hardly track back to yesterday.” “Family history is real important, my granddad says.” “My granddad never talked much of his life and nothing of his parents or brothers and sisters, if he had any. We can date him to the Civil War.” “How’s that?” “He rode with the First Nebraska Cavalry. My dad found a diary from that time tucked away in a trunk.” They came up on a rise and a gate in the line fence. Early opened the gate. He motioned for Davidson to lead his horse and her burdens through, out onto the county road. In the minutes Early had his hands out of his pockets, the cold made his fingers ache. He fumbled the gate closed and, when he caught up, he looked up to Mary Elisabet. “Missus Davidson, you and the baby doing all right up there?” “As long as I keep a hand on the saddle horn.” “Well, the Worrisome church is down there by the creek. Lights are on, so people are still there.” They set out again, easier going walking in tire tracks, the only sound the creak of saddle leather and the crunch of snow under boots. And then they heard it–singing to the accompaniment of an old reed pump organ...It came upon a midnight clear / that glorious song of old / of angels bending near the earth... “Pretty, isn’t it?” Early said. Davidson nodded his agreement. “We won’t be intruding, will we?” “Door’s open to everybody.” The straggly parade turned off at the driveway and made their way to the stoop. Early climbed the steps, stomping the snow from his boots as he went. When he opened the door, a rush of warmth and the smell of a cedar Christmas tree engulfed him, but no one sat in the pews and no one stood in the pulpit. Yet the singing continued...Peace on the Earth / good will to men / all Heaven and nature sing... He turned back, eyeing Davidson and the girl. “Not a soul in there. Tell you one thing, we’re all gonna get inside out of this cold. We’ll figure it out later. Get your wife, Joe.” Davidson helped Mary Elisabet out of the saddle and into his arms. He worked his way up the steps and inside as Early pulled the calf off his horse’s shoulders. He cradled the calf and its canvas wrapper and went on up the steps, his dog shagging behind him. After the Newfoundland cleared the door, Early reached back. He pulled the door closed. The Rural Electric’s lines had not yet reached the Worrisome church, so kerosene lamps illuminated the dozen or so pews and the front, the platform on which stood a wooden manger near the coal stove that warmed the building and, to the far side, a cedar tree decorated with strings of popcorn and chains of yellow and red loops made from construction paper. At the top of the tree resided a cardboard star wrapped imperfectly in aluminum foil. The tree did not interest Early. He pushed up to the manger and deposited his calf there, in the straw. He worked the canvas loose so the heat from the stove could get to the calf’s hair and skin, the calf so cold Early felt she was less than an hour away from death if he didn’t get her warm. He rubbed and massaged the calf, working the heat into her body. Near the manger stood a metal folding chair. Davidson hooked a foot around it and drew the chair closer. He lowered his wife onto it. “Feels some better already, doesn’t it?” he said as he helped her open the blanket with which she had wrapped her child. Mary Elisabet, smiling, gazed at the face of her boy. “Surprising he hasn’t cried, what with all that’s happened.” “You may have one of those peaceful babies, ma’am,” Early said, “let you sleep through the night.” “You have children, Mister Early?” “Little girl, about three months old.” “That’s nice.” “Yeah, it is.” He rubbed the calf more briskly. Early’s Newfoundland nosed in. He peered first at the calf, then the baby. As if he were satisfied that all was well, the dog flopped down on the platform midway between the two. “The people?” Davidson asked. “All the cars and trucks out there in the side yard, they can’t have gone home.” Early looked up from the calf, his attention drawn by the sound of cooing–Mary Elisabet cooing to her child, the baby with his eyes open, waving a tight fist at the air around him. “Joe, looks like your family’s all right.” From behind, at the far end of the church, the door swung open, and lyrics of another carol rolled in...We three kings of Orient are / bearing gifts we travel afar... Early twisted around in time to see a burly man in a great coat and an earlapper cap lead a cluster of people inside–the man, Hubert Arnold. They all stopped and gazed at the manger scene, surprise on the faces of some, awe on others. Arnold waved a hand toward the mother and child, the calf–alert now–the dog, Davidson, and Early, moisture dripping from Early’s mustache as the last of the ice melted away. “Don’t this just look like Christmas in Bethlehem.” |